Adenocarcinoma:

is used to describe epithelial tissue in a gland that has become malignant. It

is identified in a pathology laboratory and given the name of the tissue affected.

e.g. the prostate gland tumor gets the name 'prostate adenocarcinoma', because

its cells resemble the cells of the prostate.

Adenocarcinoma:

is used to describe epithelial tissue in a gland that has become malignant. It

is identified in a pathology laboratory and given the name of the tissue affected.

e.g. the prostate gland tumor gets the name 'prostate adenocarcinoma', because

its cells resemble the cells of the prostate.

Prostate Cancer. Frequently referred to as PCa, PC or CaP. As those who have

been following the steps recommended in this part of the site - going from DON'T

PANIC through SOME GOOD

NEWS! to here - will be aware, there are many varieties of prostate

cancer. Most are a slow growing cancer and there is usually an ample amount of

time to research available options. No one diagnosed with PCa should have to undertake

treatment until they understand what the treatment involves and what the outcomes

and side effects of the treatment will be. One of the RECOGNIZED

EXPERT PATHOLOGISTS is Dr. Jonathan Oppenheimer who has this to

say:

Prostate Cancer. Frequently referred to as PCa, PC or CaP. As those who have

been following the steps recommended in this part of the site - going from DON'T

PANIC through SOME GOOD

NEWS! to here - will be aware, there are many varieties of prostate

cancer. Most are a slow growing cancer and there is usually an ample amount of

time to research available options. No one diagnosed with PCa should have to undertake

treatment until they understand what the treatment involves and what the outcomes

and side effects of the treatment will be. One of the RECOGNIZED

EXPERT PATHOLOGISTS is Dr. Jonathan Oppenheimer who has this to

say:

For

the vast majority of men with a recent diagnosis of prostate cancer the most important

question is not what treatment is needed, but whether any treatment at all is

required. Active surveillance is the logical choice for most men (and the families

that love them) to make.

GLEASON

GRADES AND SCORES

If

prostate cancer cells are discovered in the biopsy material, they are evaluated

using a scale known as the Gleason Grade (GG) which was established in the 1960s

and which had five grades. As explained above, the pathologist or technician would

look for the patterns in first (prime) focus making up more than 50% of the sample

of the cancerous material. Patterns that were well differentiated, but abnormal,

were graded as 1; at the other end of the scale, poorly differentiated patterns

were graded as 5. Healthy glandular tissue is well differentiated, so a Gleason

Grade of 5 is "bad" news: a Grade of 1 is "good" news. A similar

approach is applied to the second (secondary) focus with abnormal glandular patterns

making up less than 50% of the sample. No attention was paid to a third (tertiary)

focus initially

After

each focus was graded, the primary and secondary Gleason Grades are added

together to establish a Gleason Score (GS). The Gleason Score therefore

was a scale that ran from 2 (1+1=2= "good") to 10 (5+5=10=("bad").

Typical examples of Gleason Scores would be shown as GS 3+2=5 or GS 3+3=6. These

were the most common scores until the end of the last century. A Score of 6 was

the midpoint in the overall scale. It is important to note the difference between

a Gleason Grade and a Gleason Score (which is the sum of the Grades.)

Since

the advent of PSA testing in 1987 there has been a gradual change in the interpretation

of Gleason Grades starting in 2005. The changes were formally recognized

in January 2010.

Grades 1 and

2 are no longer labeled as adenocarcinoma or cancer in material obtained through

a needle biopsy.

Grades 1 and

2 are no longer labeled as adenocarcinoma or cancer in material obtained through

a needle biopsy.

It is recommended

that some material that was previously graded as Grade 2 should now be graded

as Grade 3 and some material previously graded as Grade 3 should now be graded

as Grade 4. This means that from the time the changes were made a Gleason Score

of 6 (3+3) is the entry level for a positive diagnosis. Previously it was the

midpoint on the overall scale.

It is recommended

that some material that was previously graded as Grade 2 should now be graded

as Grade 3 and some material previously graded as Grade 3 should now be graded

as Grade 4. This means that from the time the changes were made a Gleason Score

of 6 (3+3) is the entry level for a positive diagnosis. Previously it was the

midpoint on the overall scale.

Some tunors with

a Gleason Score of 5(3+2) previously will now have a Gleason Score of 6 (3+3):

some which had a Gleason Score of 6 previously will now have a Gleason Score of

7.

Some tunors with

a Gleason Score of 5(3+2) previously will now have a Gleason Score of 6 (3+3):

some which had a Gleason Score of 6 previously will now have a Gleason Score of

7.

Since some of

the new Gleason Score 7 tumors will have an outcome more similar to Gleason Score

6 tumors, a some distinction is made between a Gleason Score of 7a (3+4) and 7b

(4+3).

Since some of

the new Gleason Score 7 tumors will have an outcome more similar to Gleason Score

6 tumors, a some distinction is made between a Gleason Score of 7a (3+4) and 7b

(4+3).

These

changes make some comparisons between current studies and old studies more difficult.

The

Gleason Score is a critical item that drives much of the decision making process.

Grading biopsy samples is a subjective process. Numerous studies show that agreement

on Gleason Scores will only occur in about 35% of cases, with roughly equal Scores

higher and lower than the original Score. It is very important to get a second

opinion on the material from any biopsy procedure from a RECOGNIZED

EXPERT before making any final decision on treatment.

For

more detailed information go to GLEASON

GRADES. BOB

PARSONS wrote an excellent piece analysing his biopsy slides and

including some good images of them. Although I labeled it BOB

PARSONS' PATHOLOGY 101 it may be a little advanced for a newly

diagnosed man.

STAGING

The

final part of an initial diagnosis is to stage the disease. This describes the

estimated extent of the cancer or the degree to which it has progressed. The old

system had four stages - ABCD to describe the progress of the disease but the

currently recommended system is known as the TNM system. The details can be read

at this link STAGING SYSTEM.

The main features are:

T refers

to the estimate of the amount of tumor within the prostate. There are four main

T stages each with three subsets. The most common staging is T1c which means there

is a tumor present, found in a needle biopsy performed due to an elevated serum

PSA but not detectable clinically or with imaging. A T2 staging is the next most

common and would refer to a tumor associated with a positive DRE. T2 tumors are

thought to be contained within the prostate gland.

T refers

to the estimate of the amount of tumor within the prostate. There are four main

T stages each with three subsets. The most common staging is T1c which means there

is a tumor present, found in a needle biopsy performed due to an elevated serum

PSA but not detectable clinically or with imaging. A T2 staging is the next most

common and would refer to a tumor associated with a positive DRE. T2 tumors are

thought to be contained within the prostate gland.

N refers

to the status of the lymph nodes near to the prostate - whether the prostate cancer

has spread there or not. It is unusual to see any N status other than NX - cannot

evaluate the regional lymph nodes.

N refers

to the status of the lymph nodes near to the prostate - whether the prostate cancer

has spread there or not. It is unusual to see any N status other than NX - cannot

evaluate the regional lymph nodes.

M indicates

if the disease has metastasized. As the tumor grows within the prostate it may

start to spread beyond the prostate gland and capsule to more distant parts of

the body. The cancer sites away from the prostate are called metastasized sites

- sometimes referred to as secondaries or more commonly 'mets'. The most common

M stage is MX - cannot evaluate distant metastasis.

M indicates

if the disease has metastasized. As the tumor grows within the prostate it may

start to spread beyond the prostate gland and capsule to more distant parts of

the body. The cancer sites away from the prostate are called metastasized sites

- sometimes referred to as secondaries or more commonly 'mets'. The most common

M stage is MX - cannot evaluate distant metastasis.

The

result of the staging is a formula such as cT2aN0MX. This would indicate a tumor

in half or less than half of one of the prostate gland's two lobes with no sign

of spread to the lymph nodes and an inability to ascertain the presence or absence

of any metastasis.

The

initial staging is known as the clinical stage and is signified by the letter

c in front of the formula mentioned above - the most common staging being cT1cNXMX

or cT1cN0M0. This means that on initial examination the tumor is not detectable

clinically or with imaging and there is no evidence of spread beyond the gland.

If

the gland is removed in surgery, another pathology report is prepared. The pathological

staging is usually different to the clinical staging and is prefixed by the letter

p. There may be significant changes in the staging which is one of the main reasons

for having surgery. A clearer picture is obtained. The pathological staging for

example might go to pT2cN1M0 - the tumor is in both lobes; there has been spread

to the regional lymph nodes; there is no distant metastasis.

It

is important to understand the difference between clinical and pathological staging

if any of the various tools - such as the Partin Tables mentioned below - are

used to try to estimate outcomes. The data in those tables is usually based on

clinical staging. After an initial diagnosis is made, a number of further tests

and scans may be ordered. The data from the diagnosis may also be used in the

various calculators or nomograms that have been developed to try and predict the

outcome of the diagnosis or treatment options.

SCANS,

TESTS AND CALCULATORS

After

an initial diagnosis is made, a number of further tests and scans may be ordered.

The data from the diagnosis may also be used in the various calculators or nomograms

that have been developed to try and predict the outcome of the diagnosis or treatment

options.

SCANS

Scans

are done in order to try to establish what, if any, spread there is into or beyond

the prostate capsule. The benefit of some of these scans is doubtful in many cases.

Some leading practitioners consider the automatic ordering of CAT and bone scans,

which occurs frequently, as a waste of money. Their necessity should be established

before the scans are undertaken.

The

Partin Tables (described further on) can help in making this decision. The chances

of there being metastases to the bone are remote with a small volume, low-grade

(Gleason Grade 6) tumor However, there is a high correlation between high Gleason

Grades (8 and above), a large tumor and the extent the disease has moved beyond

the gland. According to one leading authority there is virtually no possibility

of metastasis occurring until the tumor reaches a critical volume of about 12

cc. The average prostate gland has a volume of about 25 gm, so in this view about

half the gland would be occupied by cancer cells before metastasis occurred. In

such a case there would usually be a positive DRE (Digital Rectal Examination)

and a palpable mass. A leading expert has also expressed the view that metastasis

will not occur if the PSA is less than 50 ng/ml, unless the Gleason Score is very

high - greater than 8.

X-RAY

It

was standard practice to order X-rays as a matter of course on diagnosis. However,

the chances of any signs of spread being shown, using X-rays alone, are slim.

Since it is more usual to run other scans, there is little point in having an

X-ray. Many people strongly believe in avoiding any unnecessary exposure to X-ray

to minimize the chance of cell damage.

CT/CAT

SCANS: MRI SCANS

Although these two scans CT/CAT (Computer Axial Tomography) and MRI (Magnetic

Resonance Imaging) use differing technology, they are similar in the the sort

of output they produce. Both create a series of images, in effect showing views

of the organ being examined in "slices". The CAT scan uses X-rays to create the

images. The MRI scan uses a very strong magnetic field for this purpose. The MRI

images can be enhanced by the use of an endorectal coil. This is a small device

inserted into the rectum, which generates secondary fields.

Both

examinations can be a little intimidating for those having them for the first

time. The person being scanned lies on a small trolley, which enables them to

be moved into a large cylindrical structure containing the scanning machinery.

There is very little room in the older cylinders, especially for larger men, and

a feeling of claustrophobia can result. Newer machinery has more room. The MRI

process is noisy and operators should provide earplugs or headphones. Most men

do not have signficant pain from either procedure - just a degree of discomfort

from remaining immobilized during the scan, and the noise - but this is not always

the case.

Some

experts feel that CAT scans are only of value in the diagnostic process of advanced

prostate cancer, which is usually associated with PSA readings of 50 ng/ml or

higher and Gleason Scores greater than 8. CAT scans are highly insensitive in

detecting disease in the lymph nodes, and valueless in most patients in detecting

penetration of the capsule, which is usually the first stage of progression of

the disease. MRI scans with the endorectal coil can be much more useful but even

then will only be associated with an accuracy rate of between 75% and 90%. Both

types of scan have high false positive and false negative results. In other words

they will identify tumors which don't exist or miss ones which do exist.

There

are several other scans in use. Two for which claims are made of greater accuracy

are the COLOR-DOPPLER

and the Ferraheme. The former is not available in many institutions. It combines

two forms of scan - Ultra Sound and MRI to produce an image that, it is claimed,

show a more precise picture of any areas likely to contain cancer cells. The two

best known practitioners being Duke Bahn at Community Memorial Hospital, Ventura,

California and Fred Lee at Crittenton Hospital Medical Center, Rochester, Michigan

who can be seen talking in THIS

VIDEO. Ferraheme has yet to be approved by the FDA and is based

on the COMBIDEX

scan. The manufacturers of Combidex could not get FDA approval in the United States

and production of the scan has ceased. The Ferraheme scan is used, still in an

experimental mode, at SAND

LAKE IMAGING in Florida.

BONE

SCANS:

Bone

scans fall under the general term of nuclear medicine. The way in which these

scans work is the reverse of a CAT scan or an X-ray. In those examinations, the

radiation is sent out of a machine through the patient's body. Nuclear medicine

examinations, however, use the opposite approach. A radioactive material is introduced

into the patient's body (usually by injection), and is then detected by a machine

called a gamma camera in the case of the bone scan.

The

procedure for a bone scan involves nuclear material injected into a vein (usually

in the arm). There is a wait of two to three hours for the material to circulate

in the system. The person being examined then lies on a special table and the

gamma cameras (one above and one below) slowly track down the length of the body.

The entire procedure takes between 30 and 60 minutes. Bone metastases are usually

associated with advanced prostate cancer, so bone scans are not considered essential

for early stage disease. For men with a PSA of less than 10 and a Gleason Grade

of 6 or less, the chances of the disease having metastasized to the bone has been

estimated at less than 1% - which is equivalent to zero in medical terms.

Some

people are concerned about the introduction of nuclear material into the body,

but it is said that the radiation from this procedure is similar to that from

a normal X-ray. The material is quickly cleared from the body. There is nothing

painful about the procedure - apart from the injection, but having to remain motionless

for the time of the scan can be a little uncomfortable.

PET

SCANS

A

PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan is also a nuclear medicine imaging test

in which a small amount of liquid radioactive material is injected into your body.

It is claimed that they can identify soft tissue metastases more accurately than

other scans. PET scanners are now commonly combined with computed tomography (CT)

scanners, called PET-CT scanners.

As

is the case with the bone scan you will have to wait for about 90 minutes after

the liquid radioactive material is injected. It may be necessary to drink some

contrast material that moves through the stomach and bowel and helps to improve

the interpretation of the scan. Occasionally, depending on the medical indication

a catheter may be placed into your bladder to help improve image quality. Positioned

on the PET scanning bed, it is important to remain as still as possible during

the scan as movement can result in reduced image quality and the images may be

blurry.

If

you are having a PET-CT, the CT scan is performed first and takes less than 2

minutes. The PET scan takes approximately 30 minutes but the time will vary depending

on the regions of your body being scanned.

OTHER

TESTS

There

are two other tests that have been used in the past but which are often ignored

now and one new test. Whilst none of these tests is definitive, all can give a

little added information to help in the process of assessing status before determining

strategy. The older tests are the DNA ploidy and PAP (Prostatic Acid Phosphatase)

tests; the newer one is the PCA3 test.

PCA3

ASSAY

The

PROGENSA PCA3 assay is a urine based test that identifies the level of a genetic

component that is often present in prostate cancer. It was approved by the FDA

(Food and Drug Administration) in the United States in February 2012 and has been

in use in Europe for some time. The primary use of the assay is to assist in the

identification of cases where a biopsy procedure is justified because of an elevated

PSA or where an elevated PSA has resulted in a negative biopsy. Because the PCA3

assay result is said to be unaffected by BPH (Benign Prostate Hyperplasia) cells,

it is claimed that when used in conjunction with PSA tests, it may give a better

indication as to whether prostate cancer is present despite negative biopsy results.

The assay should not be used for men with atypical small acinar proliferation

(ASAP) on their most recent biopsy.

One

of the drawbacks to the use of the assay is that there is a requirement that the

prostate gland be "massaged vigorously" in order to get a viable result.

There may be physical problems in achieving this and it may be difficult to have

a consistent understanding of the term 'vigorous'.The clinical study of the PCA3

assay upon which FDA approval was given only included men who were recommended

for repeat biopsy. Therefore, the performance of the assay has not been established

in men for whom a repeat biopsy was not already recommended.

DNA

PLOIDY

DNA

ploidy is another test that may indicate the potential aggressiveness of a tumor

and its likely responsiveness to androgen deprivation therapies. Ploidy is a term

used to describe the chromosome content of the cell population of a tumor. Diploid

cells have normal chromosome pairs and normal DNA. They tend to grow slowly and

respond well to hormone therapy. Aneuploid cells have abnormal numbers of sets

of chromosomes. They tend to be more aggressive and not to respond as well to

hormone therapy. Aneuploid tumors are more often associated with high Gleason

score prostate cancer (8-10) and non-organ confined prostate cancer. The ploidy

test may not be done by all laboratories, but is done by Bostwick, one of the

laboratories recognized as being a RECOGNIZED

EXPERT PATHOLOGIST.

PAP

(PROSTATIC ACID PHOSPHATASE)

The

PAP (Prostatic Acid Phosphatase) test is a blood test that may be an indicator

of early metastasis (spread of the cancer) although only 75% of patients with

metastases have an elevated PAP. Few doctors seem to be aware of the potential

value of the test and may dismiss PAP as having been replaced by PSA as a prostate

cancer indicator. Like many other tests, it may be worth tracking PAP results

over time. Persistently elevated levels - 3.0 or higher - are cause for further

investigation and may indicate that surgery is not the best option.

CALCULATORS

There

are tables and nomograms that are used to try to calculate the likelihood of the

spread of PC out of the capsule of the prostate using your PSA, Gleason Ratings

and Staging. Although they look complicated at first, they are understandable

with a bit of patience. As part of your to gain a better understanding of your

condition you should do your best to do this. The PARTIN

TABLES prepared by the Brady Urological Institute was one of the

first calculators and gives a very good explanation. It allows you to make your

own calculation of the probabilities. To do this you will need your clinical staging,

your PSA and your Gleason Score. Other calculators are listed on the PALPABLE

PROSTATE site. Some of these are more complex than the Partin Tables

and need more information concerning your diagnosis.

GLOSSARY

We

have only listed some of the most common terms. There are many comprehensive

Glossaries on the Internet giving many more of the terms used. Here are two good

ones:

SUMMARY

The

process of diagnosis can be a frightening and stressful experience for most. Tests

are ordered, often without any apparent reason or explanation; results are given

in language that is difficult to interpret or understand; and all the time the

fear grows. Hopefully, this section will take some of that fear away. There is

also often a feeling that time is limited, that a decision regarding treatment

must be made very soon after diagnosis. For the vast majority of men the window

of opportunity for successful treatment is a wide one and decision-making may

safely take many months.

THREE

IMPORTANT FACTS ABOUT TESTS

There

are three basic but important facts about all medical tests:

ACCURACY

The first important

fact - No test is 100% accurate. Diagnosis is not an exact science.

The first important

fact - No test is 100% accurate. Diagnosis is not an exact science.

The

degree of error can vary considerably, depending on the complexity of the test

- and some tests are very complex indeed. Sophisticated machinery is used for

some - the maintenance of the machinery can alter the result. Chemicals are used

in other tests - the use-by date or source of these chemical agents can alter

results. Technicians run the tests - their training can alter results. The outcome

of all tests needs to be interpreted by a specialist - their expertise can vary.

All this adds up to a degree of uncertainty and explains why it is very important

to have all results checked by the most knowledgeable person available - and why

second opinions should be sought automatically.

CHANGES

The second important

fact - The value of many of the medical tests lies in measuring the change in

the results, not in the results themselves.

The second important

fact - The value of many of the medical tests lies in measuring the change in

the results, not in the results themselves.

The

most obvious example is the PSA test. It is important to measure the size and

speed of any change, since this gives an indication of the aggressiveness of the

disease. To get this measurement it is necessary to have a series of tests at

regular intervals. This may mean delaying the start of treatment but the information

is invaluable. This same concept applies to other tests.

MISTAKES

The third important

fact - mistakes can be made.

The third important

fact - mistakes can be made.

The

medical world does not differ from any other place. Human beings run it and they

can make mistakes. Get copies of all test results - ensure they are yours. If

an unusual result does not relate to other results, have a re-test in case a mistake

has been made, before taking immediate action.

When

you go to the next step you will see what we believe are actions you need to take

to enhance your chances of survival.

NOW

GO TO STEP 4 - SURVIVING PROSTATE

CANCER

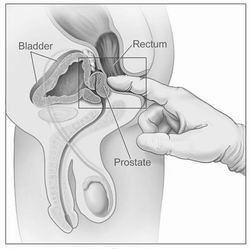

Because

the prostate gland is so well hidden, the only way it can be physically examined

by your doctor is via the rectum. If you have an understanding of where the prostate

is located, it is pretty obvious that this is the only way it can be reached.

The doctor inserts a finger to feel the prostate - trying to establish whether

there is anything unusual about the gland: a firmness or softness perhaps, or

nodules, or roughness on the surface. A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE

reveals any abnormal features even if there is no elevated PSA.

Because

the prostate gland is so well hidden, the only way it can be physically examined

by your doctor is via the rectum. If you have an understanding of where the prostate

is located, it is pretty obvious that this is the only way it can be reached.

The doctor inserts a finger to feel the prostate - trying to establish whether

there is anything unusual about the gland: a firmness or softness perhaps, or

nodules, or roughness on the surface. A biopsy may well be ordered if the DRE

reveals any abnormal features even if there is no elevated PSA.